Introduction

Somewhere in the blood-filled soft tissue of my hippocampus – a part of the brain that looks like a rather stringy chicken fillet in the shape of a seahorse – a mass of neurons and synapses have apparently been sorting out my experiences and stashing them away in various bits of my brain since the day I was born.

I never studied biology and can only imagine these neurons and synapses as being like the Numskulls in The Beezer – little men who are looking out through my eyeballs and working me from within. My Numskulls are in constant despair at the antics of their simple-minded ‘man’: ‘He’s not going to eat the entire packet of biscuits, surely?’ ‘Why does he waste so much time playing fantasy football?’ ‘Good Lord, he’s moving on to spirits now!’ They work twenty-four hours a day trying to keep me on the straight and narrow, and lurch from crisis to crisis, getting tired and making mistakes. Some memories get stashed away in the wrong place or get stuffed in so hard that they get squashed out of shape.

Taking into account that everyone’s head is full of Numskulls, each fighting a constant battle to get their man or woman to breathe, to eat, or to have an opinion about whether that was definitely offside or not, it’s easy to see how haphazard the memory system might be.

There’s a one-act play by Tom Stoppard I love, called After Magritte, in which a woman is certain she’s just seen a man in a West Bromwich Albion shirt, with shaving foam around his chin and a football under his arm, running down the street; her husband swears it was a man wearing pyjamas, with a white beard, carrying a tortoise; while her mother says it was a minstrel wearing striped prison clothes, sporting a surgical mask and carrying a lute.

At least they can all agree they’ve seen something. Something happened.

The something in question in this book is my life. Which I’m pretty sure has happened – not all of it, but quite a lot of it. Many people have been party to bits of it but I doubt they could all agree on what they’ve seen.

Years ago the Wikipedia entry on me used to say that I was born in Bolton, that I’d smash up the piano in any club I went to, and that whilst I was a student at Manchester I shacked up with Viv Albertine, the guitarist from The Slits. Well, I was born in Bradford, I’ve never attacked a piano – I love pianos and wish them no harm – and I’ve never even met Viv Albertine, much though I would’ve loved to have shacked up with her in the mid-seventies.

Back then I tried to edit the page but the Wikipedia moderators – self-appointed guardians of the truth – always took my corrections down. I sent a message saying I actually was Adrian Edmondson. Oh, how they scoffed. They said it was obvious from what I’d written that I knew absolutely nothing about him, and they blocked me from editing the page thereafter.

Of course, on one level they might be right – do I really know anything about myself? Really? Deep down? What would my psychiatrist say?

I know I’m not the bloke on the Wikipedia page, which, amongst the strange emphasis and vague biographical errors, is mainly a list of programmes I’ve been in. The list is more or less accurate, but I’m not a list of programmes.

I’m not The Young Ones – I mean of course I was in it, I was bloody good in it actually, but making the two series of The Young Ones took up precisely fourteen weeks of my life. Or to put it another way – less than one half of one per cent of my life.

So far.

In 2016 I adapted William Leith’s book Bits of Me Are Falling Apart into a one-man play. It took six weeks to do the adaptation, four weeks to rehearse it, and it played for a further four weeks at the Soho Theatre, a small London venue, to a total of around 2,500 people. It took up the same amount of my life as The Young Ones. I’m not expecting you to think it’s as noteworthy, but the Numskulls in my head have given it exactly the same amount of space.

I know one thing for sure, this is not the most linear autobiography you’ll ever read. It doesn’t start at the beginning and plod resolutely through to the end. My memory isn’t linear – it flits about from one subject to another, back and forth through the years. So this book is not particularly coherent, but then neither is my life. It’s all about the tangents.

It’s also littered with references to songs that were at some point number one in the charts. Whenever I hear a song it gives me more context about the time I first heard it than any potted history might do – I can see the colour and the shape of cars, the way people dressed and behaved, and I can feel how people were thinking at the time. So every song title in this book is like one of Proust’s madeleines to me – it takes me straight back to where I was and what it felt like. I hope they help you in the same way. Or at least bring you joy.

I hope this book is about more than just me, I think it might be about you too, because most of us have lived through the same era. I hope it makes you laugh occasionally, I hope you enjoy the diversions into history, cooking and pop music, because it’s basically everything I know about being a human being born in Britain in the mid twentieth century.

My memory is like a misprinted dot-to-dot puzzle – some of the dots are missing but my brain fills them in for me. Which sounds imprecise, but I know that what I remember is true to me. This is how it felt to me. I have lived my life thinking all of the following to be the truth, which in some way makes it the truth.

On the other hand I often forget my own children’s names, and can never remember where I left the bloody keys – so good luck, and caveat emptor.

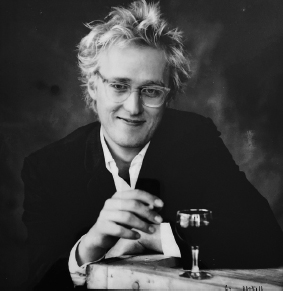

My daughter Freya says she’s always loved this photo of me because I look like a Danish philosopher. If only. I discuss my frustrated claims of Viking ancestry later in the book, and only have a puny degree in drama not philosophy, but you learn the odd thing by simply hanging around for sixty-six years. So perhaps there is some philosophy in here too. And I like the Danes.